توتانخآمون یا توتعنخآمون (یه معنی پنداشت زنده آمون) بین سالهای ۱۳۳۳ تا ۱۳۲۷ پیش از میلاد پادشاهی میکرد و یازدهمین فرعون مصر باستان از دودمان هجدهم یا همان پادشاهی نو شناخته میشود.

آرامگاه او در روز ۴ نوامبرسال ۱۹۲۲ در دره پادشاهان توسط هاوارد کارتر بهتقریب دست نخورده یافته شد. این یافته را نشریات پخش کردند و توجه عامه به مصر باستان بسیار افزایش یافت.

توتانخآمون در مقایسه با دیگر فرعونهای بزرگ تاریخ مصر ثروت عظیمی نداشت، ولی آنچه گنج او را از سایرین تمایز داده است مقبرهٔ دست نخوردهاش است که در تمامی این سالها از هر دزدی به دور مانده است و این در حالی است که آرامگاههای فراعنهٔ بزرگ هزاران بار در طول تاریخ مورد دستبرد دزدان قرار گرفته است.

آنچه آرامگاه توتانخآمون را از دستبرد نجات داد ورودی کوچک و پنهان شده در زیر سنگها بود که در طول همهٔ این سالیان جلب توجه نکرد. بهعلاوه، توتانخآمون دورهٔ حکومت کوتاه و بیغوغایی داشت و گنجینهٔ او عظیم نبود؛ به همین دلیل پس مدت کوتاهی به فراموشی سپرده شد.

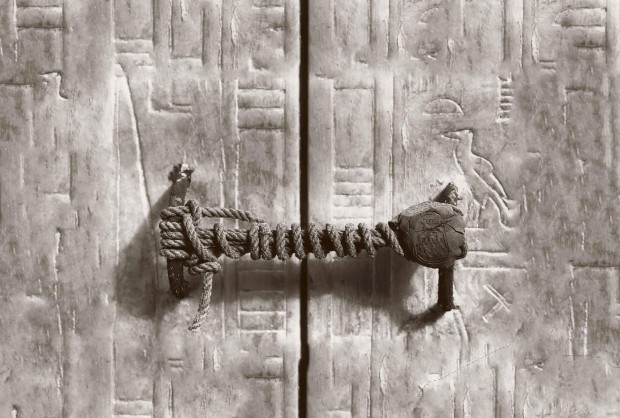

حالا تصور کنید که به عنوان یک باستانشناس روبرو مهر و مومی ایستاده باشید که ۳۲۴۵ سال قدمت داشته باشد و دست نخورده باشد، این دقیقا حال و هوایی بودن که هووارد کارتر در سال ۱۹۲۳ در جلوی آرمامگاه «توت» داشت.

عکسی که میبینید در همان سال توسط عکاسی به نام هری برتون گرفته شده است. تا آن زمان البته دو بار معابد پیرامونی معبد اصلی که در آن تابوت و جسد مومیایی قرار داشت، مورد سرقت قرار گرفته بودند، اما این معبد اصلی دستنخورده باقی ماده بود.

خیلی هیجانانگیز است که آدم مهر و مومی را ببینید که ۳۲ قرن تمام تاب آورده است و سؤالی که مطرح میشود این است که این طناب چطور در این زمان طولانی پوسیده نشده است.

پاسخ در دو چیز نهفته است:

۱- شرایط خشک بیابانی حاکم در مصر که عاری از هرگونه رطوبت بود.

۲- خود معبد عایقبندی شده و هوا و اکسیژن به داخل آن راهی نداشت و بنابراین باکتریهای هوازی نمیتوانستند مواد آلی را بپوسانند.

هووارد کارتر در حال بررسی تابوت توتانخآمون

در معابد و آرامگاههای مصر پیدا کردن چوب و طناب و رنگینههای آلی، چیزی کاملا مرسوم است، اما در مقام مقایسه تقریبا هیچ یادگاری آلیای از تمدن مایایی باقی نمانده است، چرا که شهروندان این تمدن در میانه جنگلهای پررطوبت آمریکایی مرکزی زیست میکردند.

عکسی که در این پست دیدید، در زمان کشف مقبره، توسط نشنال جئوگرافیک منتشر نشده بود و تنها در سال ۲۰۰۳ بود که به صورت عمومی از این عکس جالب رونمایی شد.

This Is The Actual Seal That Secured King Tutankhamun's Tomb

This Is The Actual Seal That Secured King Tutankhamun's Tomb

Imagine being an archaeologist exploring ancient shrines in Egypt and stumbling upon this 3,245-year-old unbroken seal. Such was the sight that greeted Howard Carter in 1923 as he prepared to enter King Tut’s astounding shrine for the first time.

This incredible photograph was taken by Harry Burton in 1923. It shows a still-intact seal made from rope securing the doors to the second of four nested shrines in Tutankhamun’s tomb. The necropolis seal depicts captives on their knees, and Annubis, the jackal god of the dead.

King Tut’s outermost shrine was opened and looted twice during ancient times, but the doors of the second of the huge shrines of gilded wood containing the royal sarcophagus still carried the uncompromised seal — an indication that the contents were untouched and intact.

The door was eventually opened by the famous archaeologist and Egyptologist Howard Carter, leading to the discovery of a spectacular trove of ancient treasures.

So how did the rope last for 32 centuries without falling apart? A post from Rare Historical Photos explains:

Rope is one of the fundamental human technologies. Archaeologists have found two-ply ropes going back 28,000 years. Egyptians were the first documented civilization to use specialized tools to make rope. One key why the rope lasted so long wasn’t the rope itself, it was the aridity of the air in the desert. It dries out and preserves things. Another key is oxygen deprivation. Tombs are sealed to the outside. Bacteria can break things down as long as they have oxygen, but then they effectively suffocate. It’s not uncommon to find rope, wooden carvings, cloth, organic dyes, etc. in Egyptian pyramids and tombs that wouldn’t have survived elsewhere in the world. Egypt’s desert conditions made possible the preservation of far more organic material than would have otherwise been the case. This in contrast to, say, Maya sites in Central America which are far younger, but from which almost no organic material has been recovered. The main difference is jungle vs desert conditions.

The photo, which somehow didn’t make it into National Geographic’s original coverage of the dig, was finally released to the public in 2003.

Photograph by Harry Burton, Griffith Institute, Oxford 1923.

گجت نیوز آخرین اخبار تکنولوژی، علم و خودرو

گجت نیوز آخرین اخبار تکنولوژی، علم و خودرو