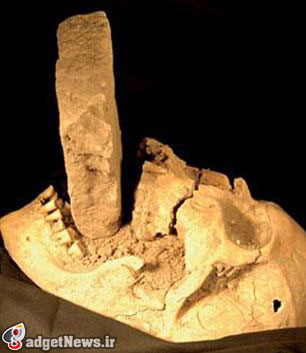

باستانشناسان آن چه را که به باور آنها یک گورستان خونآشام است را در لهستان کشف کردند.تیمی از مورخان گورهایی را در جنوب شهر گلیوایس کشف کردهاند که شامل چهار اسکلت همراه با سرهایشان است که این سرها بین رانهایشان قرار دارند.باستانشناسان هیچ اموال زمینی مانند جوارات، کمربند یا سگک را همراه با این اسکلتها نیافتهاند.

بقایای این گورها برای انجام آزمایشهای بیشتر تحت مطالعهاند و دانشمندان تخمین میزنند که مالکان اسکلتها حدود قرن شانزدهم میزیستهاند.سر بریدن یک خونآشام مشکوک عملی رایج در قرون وسطی بوده زیرا تصور میشد این تنها راه برای اطمینان از این است که آنها مرده باقی میمانند.

سال گذشته نیز باستانشناسان بلغاری مدعی کشف جسد دو خونآشام در نزدیکی دیری در سوزوپول شده بودند که هر دوی آنها بیش از 800 سال قدمت داشتند و میلههای آهنی سنگینی در قفسه سینههایشان فرو رفته بود.بوزیدهار دیمیترف، رییس موزه ملی بلغارستان، اعلام کرد که حدود 100 جسد خونآشام طی سالهای اخیر در این کشور کشف شده است.این موضوع نشان از عمل رایج کشتن خونآشامها در روستاهای بلغارستان تا دهه اول قرن بیستم است.

حتی امروزه نیز خونآشام تهدیدی بسیار جدی در اذهان روستاییان در تعدادی از دوردستترین جوامع اروپای شرقی به شمار میآید و در آنها صلیبهایی تولید میشوند و اجساد برای بیرون کشیدن میخ از درون قلبشان، نبش قبر میشوند.ایده خونآشامهای مکنده خون گوشت زندهها به هزاران سال پیش بازمیگردد و در بسیاری از فرهنگهای باستان رایج بوده است.

باستانشناسان اخیرا سه هزار گور را در چک یافتهاند که در آنها صخرههایی بر روی اجساد قرار داشت تا از برخاستن مردگان از گورهایشان ممانعت شود.ظهور مسیحیت فقط افسانههای خونآشام را تغذیه کرد زیرا این موجودات دشمنان مسیح به شمار میآمدند و ارواحی بودند که از اجساد افراد شرور برخاسته بودند. این خونآشامها جادهها را برای مکیدن خون انسانها و حیوانات جستجو میکردند.

در قرون وسطی و زمانی که کلیسا بسیار قدرتمند بود و تهدید نفرین ابدی خرافات را در بین روستائیان افزایش داد، ترس از خونآشامها بسیار معمول بود.در تعدادی از موارد، مردگان با آجری در دهانشان دفن میشدند تا از برخاستن آنها برای مکیدن خون افرادی که از طاعون هلاک میشدند، جلوگیری شود.

گفته میشود، غربیها در قرن 18 و با سفرهای شهروندانشان به اروپای مرکزی و شرقی از وجود خونآشامها آگاهی یافتند.

منبع : dailymail

Pictured: 'Vampire' graves in Poland where skeletons were buried with skulls between their legs

Decapitating a suspected vampire was common practice in medieval times

It was believed removing head ensured vampire would stay dead

They are believed to date from around the 16th or 17th centuries

There were no earthly possessions, such as jewellery, belts or buckles

Archaeologists have unearthed what they believe to be a vampire burial ground on a building site in Poland.

The team of historians discovered graves containing four skeletons with their heads removed and placed between their legs near the southern town of Gliwice.

Decapitating a suspected vampire was common practice in medieval times because it was thought to be the only way to ensure the dead stay dead.

Eerie: The team of historians discovered graves containing four skeletons with their heads removed and placed between their legs near the southern town of Gliwice, Poland

The dead stay dead: Decapitating a suspected vampire was common practice in medieval times because it was thought to be the only way to ensure the dead stay dead

No possessions: The exact fate of the skeletons is yet unclear, but the archaeologists noted that, apart from being headless, there was no trace of any earthly possessions, such as jewellery, belts or buckles

The exact fate of the skeletons is yet unclear, but the archaeologists noted that, apart from being headless, there was no trace of any earthly possessions, such as jewellery, belts or buckles.

'It's very difficult to tell when these burials were carried out,' archaeologist Dr Jacek Pierzak told the Dziennik Zachodni newspaper.

The remains have been sent for further testing but initial estimations suggest they died sometime around the 16th century.

Even today, the vampire remains a very real threat in the minds of villagers in some of the most remote communities of Eastern Europe, where garlic and crucifixes are readily wielded, and where bodies are exhumed so that a stake can be driven through their heart.

The notion of blood-sucking vampires preying on the flesh of the living goes back thousands of years and was common in many ancient cultures, where tales of these reviled creatures of the dead abounded.

Archaeologists recently found 3,000 Czech graves, for example, where bodies had been weighed down with rocks to prevent the dead emerging from their tombs.

The advent of Christianity only fuelled the vampire legends, for they were considered the antithesis of Christ — spirits that rose from the dead bodies of evil people.

Such vampires would stalk the streets in search of others to join their unholy pastime of sucking the lifeblood from humans and animals to survive.

In medieval times, when the Church was all-powerful and the threat of eternal damnation encouraged superstition among a peasantry already blighted by the Black Death, the fear of vampires was omnipresent. In some cases, the dead were buried with a brick wedged in their mouths to stop them rising up to eat those who had perished from the plague.

Records show that in the 12th Century on the Scottish Borders, a woman claimed she was being terrorised by a dead priest who had been buried at Melrose Abbey only days earlier.

When the monks uncovered the tomb, they claimed to have found the corpse bleeding fresh blood. The corpse of the priest, well known for having neglected his religious duties, was burned.

But vampiric folklore largely flourished in Eastern European countries and Greece, where they did not have a tradition of believing in witches. And just as with witches in England, Germany and America, the vampire became a scapegoat for a community’s ills.

The ‘civilised’ world came to learn of vampires in the 18th century as Western empires expanded and their peoples travelled to remote parts of Central and Eastern Europe.

With the spread of Austria’s empire, for example, the West became aware of the story of the remote village of Kisilova (believed to be modern-day Kisiljevo in Hungary) after it had been annexed by the Austrians.

گجت نیوز آخرین اخبار تکنولوژی، علم و خودرو

گجت نیوز آخرین اخبار تکنولوژی، علم و خودرو